Homeless Boyfriends Do It Better

I.

My boyfriend had $13. Not like, in his pocket—to his name. Which hadn’t been changed from his birth name to his real name, because that cost $124—plus $5.50 for every certified copy, required to change any IDs—in the state where he lived, to the extent that houseless/travelers staying places they can be tossed from at any time live anyplace. But last winter, when I was driving the van West lived in for years—and couldn’t afford to register or insure—and we passed two travelers holding a sign asking for change, he told me to pull over.

He gave them a couple of singles wrapped in a $50 bill. He had found the latter, and told them he wasn’t sure if it was real or not but hoped it was, wishing them a great day.

When we pulled away, I said that I didn’t understand why he did that, especially given the worldly boosters those two had that he didn’t: whiteness, cis maleness. He responded that he could see they didn’t have any local support, because they had all their bags with them, which meant they didn’t have anyone friendly enough to leave them with while they spanged (“spare” + “change,” long A). And if he had it, he said, he always kicked money down to fellow travelers, especially if they were committed to the lifestyle. These two, he pointed out, had faces covered in tattoos in a way that suggested they weren’t likely to try or succeed in the traditional workforce, probably ever.

My point, as a person earning well below the federal line for a couple of years, is not that poverty is glamorous or noble. I have generally experienced it as a kind of steady, low-grade suffocation, like the air is always just about to run out. West had been homeless (his word) way longer than I have been homeless (social services’ word), and he found it stressful, too. But he also will not Do Capitalism, which we good liberals all agree is bad for almost everyone but do anyway. The career I left, to be fair, was also often suffocating and stressful, if in entirely different ways. Certainly the hamster wheel of high bills I spent with the money from it was, none of which made me feel valuable, not really. Not in the way that matters: unconditionally.

West knew from more experience that enough oxygen shows up in time. And anyway, he was true to his principles: He did have money right now. At that moment, in addition to having food to eat and gas in his tank, he had $13.

II.

AS I PREPARED to leave Washington to visit him last fall at the Oregon “sanctuary” where he parked and lived, I made a list of things I needed to do, like a good overachiever. Overachieving had been both my cope and most of my personality for decades, and every day, I still woke up feeling the fast-moving frenzy of Getting Things Done bubble up in my veins, a panic-adjacent sort of agitation that animated my movements since I was a teenager. Even a year after I moved into a vehicle and cut my expenses by 90 percent, which was five years after I’d stopped being able to work full-time, the feeling raged as hard as ever, parked though I was on a rural farm where no one is in a hurry.

It was while getting ready to go see West that I looked at the to-do list on my dry-erase board one day and thought, for the first time in my life: I have way more than enough time to do these things. Because I did. And so, I relaxed a little.

I had another note among the chores on my dry-erase board. What’s easy/fun/works for me, I’d written across the bottom quarter, a sort of counterbalance to the incessant WHAT SHOULD I DO/DO I NEED TO BE DOING RIGHT NOW running in my head—an attempt to reorient myself around a different kind of question. But I rarely actually asked it, and even less frequently followed the answer.

West didn’t have any money. But what he had in abundance, I imagine partly because he’d long detoxed from the workforce, is constant orientation to actual humanity in a way I’d never witnessed, and I’ve been a lot of places. When I returned to the “sanctuary,” he was the caretaker of its vast acres, empty for the end of the season, and I more fully entered his orbit. In the mornings, I woke up in my RV with a head full of ideas about how much I needed to do, starting to feel That Feeling, immediately attended by stress about whether I had the energy to do all of it. There is always work I could be doing, and I cannot work like I used to. Like I burned myself out doing.

One day toward the beginning of my two-month visit, I woke up to pleasant autumn sun coming through my windows and decided to give myself two goals, and two only: Read in the garden, and write one email. I guess the third, implied goal of not trying to do more than that was actually the biggest one. I let myself ease into my day slowly, reminding myself one million times (approximate figure) that those were my only two goals as over and over I started beating myself up for not doing more, faster, and better, repeat.

I ended up lying down for a long time after breakfast. I needed to do it. But I calmed my fretting about doing it by reminding myself, over and over: Only those two goals. Those two goals only. By the time I got them done—what else was I doing? Cooking. Showering. Watching The Voice. Eating. Talking. Journaling?—the day was over.

This is a depressing sentence, but it never occurred to me that someone could love me if I did as little as that.

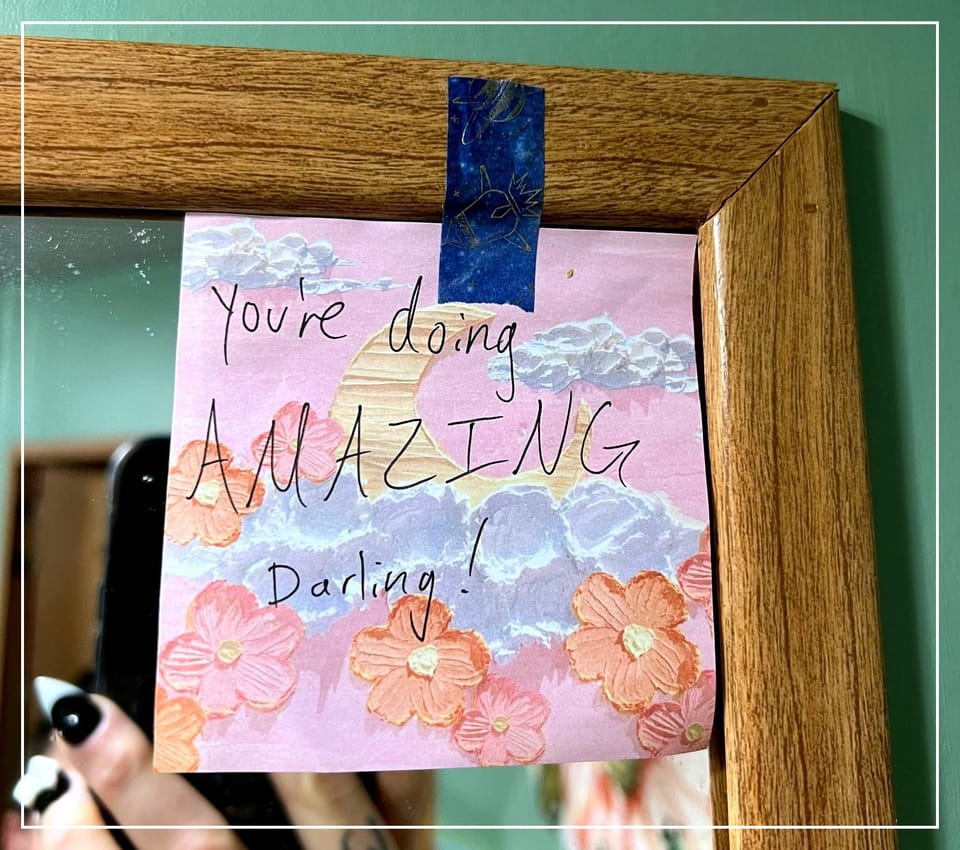

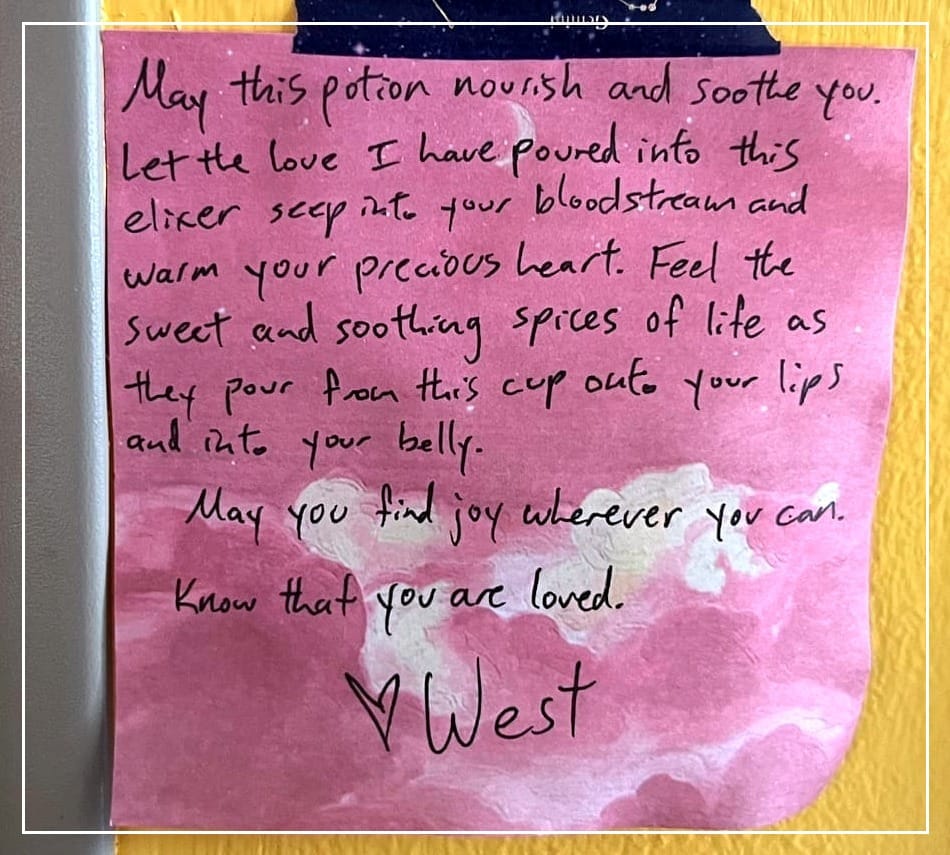

West did. One day, I took a nap after breakfast—it was a hard day; the depression that follows my flashback bouts can be paralyzing, not that I need to justify napping after breakfast, which I am definitely doing right now—and he brought a smoothie over and put it in my fridge so I could have it when I woke up. He’d made it with ingredients proffered from the land’s extremely modest grocery budget, and it was bright with spice and citrus and a note with a well-being spell taped around it.

“I’m so proud of you,” he kept saying when he hung out. When I often couldn’t get up for days and days and days on end. It wasn’t because I graduated summa cum laude from college. It was because I’d given myself the gift of a really comfortable motorhome to rest in, and was resting in it.

“My most singular, agonizing wish since I was a child was to be safe and to be loved,” I wrote in a GQ article five years ago, noting that I couldn’t transition until and unless I believed those things would be possible after. I barely believed it then. I also believed—I still do, on some levels—that both those things required money.

But those two months, I woke up or we woke up together, and West made the world’s slowest breakfast: whenever he was ready to cook, whatever he was in the mood for with whatever was available on the land. The conversations we had about what we’d have for breakfast lasted longer than it would take me to make and eat and clean up breakfast on my own, like it was—because it always was, since grade school—a thing I had to get done to get to the next thing. The longer it took, the more abundant and delicious it ended up being, thin-slicing a found red onion here, layering dressings and sauces from the fridge onto eggs on a flavored bagel there.

When we made our way to the local WinCo together for groceries one day, I had to check my constant strive for efficiency even when it was totally needless, for timeliness even when it didn’t matter. (I associate it, rightly or wrongly, with being Midwestern; when we did have to get somewhere in a timely fashion, admittedly not West’s strong suit, I hustled us along in a gear we called Full Cleveland.) He proceeded around the store at a leisurely stroll, his giant, senior poodle leashed to his waist, making friendly conversation with retirees slowly shopping alongside us, and I fidgeted next to them like a kid trying to behave in church, restraining myself from running ahead to strike items off the list more quickly.

When we walked out 90 minutes later, I told him that if I had gone by myself, it would’ve taken 35 minutes. He said that if he had gone without me, he’d have taken three hours.

III.

I wasn’t from a family that didn’t say I love you. As a longtime serial monogamist, I had lots of boyfriends and multiple husbands who collectively told me one million times (possibly exact figure) that they loved me. But in the immortal words of Inigo Montoya, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

It means, in my experience, that the people closest to me want me doing, or being, something else. I brought that to the people I loved in turn: I can fix him! He’ll change! Everything will be perfect when he’s just…extremely different than he is right now! In the closet, I tried to earn love, with sex and with achieving, with awards and accolades, piling them up with my growing IRA like proof of my worth. Out of the closet, I showered sex and life savings on my first post-transition boyfriend, who always needed more than what I gave (he’d be less moody and resentful toward me, he said, if we lived in a mansion with more personal space).

West was my second. And by the time we became boyfriends, I’d long been broke. “Are we trying to pay for gas, or gas-jug?” he asked, grinning, when one day I suggested we fuck everything and drive my house to Costa Rica. Paying for gas is faster, and involves sticking in a credit card. Gas-jugging involves hanging around whatever gas station you stop at asking strangers to buy you some. It was how he’d always gotten everywhere, and it takes much longer, given all the nos, but, he assured me, it always eventually ended in a yes.

I could see it, the two of us sitting in the dusty heat outside a gas station in the middle of California or Texas or wherever we ran out of fuel, loving each other as we asked for help. This scenario of being forced to beg for basic necessities had always seemed like my absolute fucking nightmare, but suddenly I could see it for what it was: Not that big of a deal. Just an experience. In it, we’d have not just each other but also housing, for god’s sake—and nice housing at that. I’d met some of West’s other homeless/traveler friends one night, who all lived in cars or vans with no appliances, and one of them offered me a packed bowl through my open RV window as they stood outside it. When I declined, they responded, “You live in a mansion, and you don’t smoke weed in it?”

I had never, ever, before the moment West brought up gas-jugging, considered that a partner and I could make total-brokeness part of our adventure. Considered that I could be accepted and embraced and wanted just as I was when what I was was broke. Considered that I could experience it as something a partner and I were in together and to any extent unbothered by.

I hadn’t yet consciously considered that I could bring total acceptance to my relationship with myself. But in that moment, some super heavy veil of impossibility that got brainwashed into my perspective by ableist supremacist capitalism lifted, leaving an unfamiliar brightness in its wake.

IV.

I caught myself just now, literally as I was writing this, feeling the push to hurry up, complete this so I can move on to another thing. I know why. I’m pushing myself to become something else. Get past what I am, and so what I am doing, at any given moment. But being safe and loved starts with me.

WHAT’S MOST JOYFUL? my dry-erase board asks, in all caps. WHAT’S THE GAYEST? thing I could be doing with this given moment, what FEELS MOST ALIVE? One day, West wrote You are loved ♡ underneath it, and even after we broke up, I left it there for a long time.

After I returned to Washington in January, one of my other land-mates was over for drinks, and I started talking about what I can do versus what’s best for me. She got up and wrote on my board, honor what’s true ♡. She squeezed it into the space next to where I’d scrawled HAPPIEST, as in, “What would make me the.” The answer isn’t trite or navel-gazing. What would I do if I already believed, regardless of how it looked to anyone else, that what felt joyful to me—versus what I think I “should” do—was already perfect?

Was holy.

After the moon showed me that West was my teacher, to him, I was the best boyfriend I’ve ever been: I was better able to accept him as he was, though his lifestyle was oppositional in the extreme to all of my conditioning, to anyone I’ve ever dated. It didn’t mean I liked it all the time. Or was a perfect partner. But every day, I operated with the understanding that who he was right then, and might always exactly be, was perfectly sacred.

I have never been nearly as good of a boyfriend to myself as I have to anyone else. I said way shittier stuff to myself in my head than I would ever say out loud to another person, maybe the die-hardest habit I’ve tried to break so far. But these days, I increasingly nail it. What do you need, sweetie, I ask myself constantly, not judging the answers, however unconventional. However anticapitalist.

Shortly after my return home, I woke up wanting breakfast nachos. And so, I made them. One of my land-mates had found a giant pile of ripe avocados in the parking lot of the bourgie grocery store in town and handed them out when she got home. I realized I had half of a tomato left over from the food bank, and some shallots West had left in the dry goods/snacks cubby above my door along with one of those little lemon-shaped squeeze bottles of lemon juice in my fridge, so I made myself guacamole without hurrying to get to the next thing, a practice I could have implemented as a childless freelancer ten years ago but even up to lately couldn’t have done without rushing and judging myself for not moving fast enough. But that day, I stood in slow-moving confidence that I was, and guacamole is, worth the time. When I put some in my mouth to test the seasoning, it tasted so fresh I started crying.

The next day, I went to the grocery store by myself. As I got ready, I felt the Full Cleveland come on: big-hustle energy, from which I’m apparently in permanent rehab, because there was no set time I needed to finish. I run all my errands by bike, which contributes to the time and energy they take and I was already hungry and if I left right now, I thought, when would I squeeze in lunch?? I was exhausted before I even left the house. And I stopped, and reframed.

What if going to the grocery store wasn’t something I had to get done today but was the thing I was doing today?, I thought. I would go in and buy a sandwich and eat it at one of their cute tables out front. I would go back in fed, and then, and only then, complete the shopping and bike home. I would take the time to put on a little more jewelry, a cuter jacket (all faux fur, instead of just faux-fur trim), since there was suddenly no emergency, no crisis like I’ve been constantly creating out of addiction and habit. I would give myself a fucking break.

As I stood near the deli counter waiting for my sandwich (pro tip: Cold prepared foods and sandwiches are EBT-eligible. If you have them heat it up, the government WILL NOT pay for that shit for poors), I looked up to see an older woman steering her grocery cart toward me.

“I’m gonna be fresh,” she said, as we made eye contact.

She pulled her cart right up next to me. “The world needs people like you,” she said. “I was just looking at all these other women in here and thinking, ‘We’re all just trying to get through the day, running around in our leggings.’ And then I see you.”

“I’m wearing leggings, too,” I said, trying to be encouraging.

“You’re wearing them different.”

Today, I woke up at dawn to a cat jumping on me, and dragged myself from bed to take him for a walk around the farm. Then I came back and ate organic chocolate pudding for breakfast (thanks, food bank!) and went back to sleep, which is one of my favorite things to do, though it means I don’t really get up until around 11, but it makes me so happy—after so many years of waking up exhausted for school, after harrowing nights of unspeakable torture, then as an adult for long coach flights to war and devastation and birders with a death wish—and if I don’t get up until noon for the rest of my life, so. be. it. I worked, I fed myself, I watched a terrible movie about a bartender becoming an astronaut. Tonight all I wanna do is watch the new Godzilla movie on HBO and get a little high. I don’t care about Godzilla, and I don’t imbibe much cannabis. But I’ve got a TV and a mansion, and I am going to smoke weed in it.

Member discussion