An Incomplete List of Gifts from Men I’ve Kissed

DINNER.

MEN I’VE kissed—and, let’s just be honest, often fucked—have bought me dinner. Dinner in New York, in San Francisco.

Dinner in Paris. Dinner in Belgium, in the Netherlands, in Switzerland. Dinner in Haiti—in two different cities. Dinner—and breakfast, and for my friends, too—in Los Angeles. Dinner in Marin, and a weekend in a big house there with a hot tub. Enough top-shelf booze, accompanying all of the above, to kill someone.

A plane ticket to Europe. A fancy hotel and several meals in LA (not related to the above meals in that city). A whole-ass car, if you count my dad as someone I’ve kissed, and fucked; you probably should, since while being raped doesn’t count as sex, he remains the longest contiguous sexual relationship of my life, and while I wasn’t his only kid, I was the only one to receive a brand-new Pontiac Grand Am with a giant bow on it for my sixteenth birthday.

WHEN I BOUGHT my adorable electric BMW in 2021, I was already running out of money. But my credit score didn’t know that.

“You’re approved,” the salesman said when he called me on my way home from the test drive at the dealership. I certainly wasn’t the first gay who’d ever walked in there, and I probably wasn’t the first trans person, but I remember feeling like I was doing something illicit while I was filling out the paperwork for the loan, like the entire history of trans people, let alone trans queers, being cut off from jobs and income and financially secure lives was peeking over my shoulder. When I got the call about the approval, driving away in a borrowed car shortly after I’d left, I felt a weird peace spread through my body.

When we hung up, I smiled as I barreled down the freeway, feeling warm and safe.

A year later, when I was down to the last of my savings after financing yet another nice Bay Area apartment—and my nice car, which I used to zip around to errands and lifesaving therapeutic bodywork—I asked myself if I was about to be the kind of homeless that didn’t involve shelter. It was clear that I had to stop taking assignments. Was I going to just sell everything and take the meager proceeds as food money while I lived on the beach in Santa Cruz? I pictured myself sitting there on the sand, no belongings, no roof. No sense of obligation or safety. It felt sort of freeing when I felt into it, but also like my worst nightmare. I’d be spending so much energy surviving that level of insecurity that I wouldn’t be able to do much else.

I HAD BOUGHT myself so many fancy things.

I’d bought several apartments’ worth of furniture. Multiple brand-new nice couches. A used custom couch. An adjustable standing desk, $1,800 MSRP, secondhand on Craigslist, a 1940s Mission desk at an Oakland antique shop, French-country wooden chairs that were available only on order after a long waitlist. An enviably bohemian-chic farm table. Several one-of-a-kind lamps.

“Treat this [vintage frosted-glass] shade like it’s the only one on the planet,” the woman at the lamp shop where I got one of them serviced said. She warned me that people with nice lamps didn’t put them out of the way of their clumsy husbands, who were always knocking them over and breaking them.

“Ooh, this is a good pull!” she’d said already, commenting on how much better the chain was than most from that time period.

I bought cars. Cars for me, three different trucks for my second husband, and a dream backpacking trip across the Annapurna circuit. I’d bought my first husband a six-month trip around the Pacific. Divorced from both of them, I bought an ancient Japanese soy-sauce barrel that I used as an end table. I had an ex-boyfriend drive me to pick up a bookshelf made of Indonesian salvaged wood, which’d had a sliver sliced off in transit; they gave me $100 off, not enough for the damage, but I’d been waiting months and traveled a long distance so bought it anyway, eager as I was to have my 2021 Marin apartment—my 21st rental in 23 years—fully finished.

And so, it soon was. Art hung. Plants and altar arranged. “Can you imagine if this was your view?” another trans person asked when they came over. They were younger, which means that, unlike me, they’d grown up with the internet showing them successful trans lives. And their parents had given them Tesla stock as a teenager. Still, that’s how unfathomable my well-appointed trans existence was to even a Gen Z queer who was raised in one of the five richest counties in America.

“Oh wait,” they said, remembering whose (rented) house we were in. “This is your view.”

THIS WAS WHAT I was working for: Everything in that perfectly appointed place. The deck was strung with sweet lights, hovering above a hard-to-find, round outdoor bamboo daybed with comfy water resistant cushions, facing a light-up Buddha holding an overflowing cup/water feature, which, even as I type, I realize is something that would’ve made Buddha roll his eyes right out of his head.

But this, I thought, was what I thought I wanted all along.

Years before, still married and a few weeks after my very first therapist-assisted psychedelic session, I wrote a journal entry, in a journal I’d bought explicitly at the advice of said psychedelic therapist. At the time, I was in the midst of a protracted house-hunting mission with my second husband.

“I could, every ten years, find myself with a husband and a possibility for peace and land and permanence and when I’m so close, finally see that the thing I’ve always thought I wanted I don’t really want at all,” I wrote.

The next entry is a pro and con list for killing myself.

It’s a strange thing, to be terrified of not wanting the things you thought you wanted. Another way of holding that realization, of course, would be that it’s liberating. Some of it, I get. Realizing you’re trans is—I’m just going to acknowledge, given how our world holds transness—an absolute bitch. Realizing you need not just to transition but to figure out how to procure yourself a couple-hundred-thousand-dollar penis and divorce yourself from the ways you’ve earned money is not-great news in a lot of objective ways.

“I just wanna go back to the land of khakis,” said one trans friend, one who was tangling with her own transition needs late in an expensive life, as we drank one night on the deck of an apartment I would soon be unable to afford. She was recognizing already, having just started coming out, the ways she didn’t fit into the fancy cis white world she’d moved and built her business in for decades.

She was wearing a long, frilly dress she’d pulled out of my closet and put on her 50-year-old frame; the former, she loved, while the latter had a long way to go, which was an issue for her straight lover.

I understood, and I said so. I’d long been learning by then that I was never going to be as universally desirable, either personally or professionally, again.

“BEST MONEY I ever spent,” my new friend Sky said last weekend, after a tow truck he’d paid $500 pulled my house off a hill’s edge when the retaining wall on his driveway gave way.

I’d never been to his house before. He’s single and trans and gay and bought it all by himself; it cost the kind of money that where I come from, even most straight cis people with double incomes don’t have.

I offered to split the tow-truck cost with him, but he wouldn’t have it. I asked him, after Bessie was back on solid ground and we were having cocktails around the firepit on his back deck, if we were in the kind of friendship where we wanted to explore a sensual connection. We’d hung out three times. While I was clear I didn’t want to have sex or get married, and said so, I wondered what would happen if we put our mouths together, and I said that, too.

On our second hangout, a few weeks prior, we’d gone to brunch. He’d paid; he’d also picked me up in his shiny new truck, and when he’d come in while dropping me off, I’d noticed the shape of his thighs under his jeans, strong and sturdy. I did notice that I didn’t start noticing that until he’d spent some money on me.

“That’s it,” my Bay Area therapist said in a voice memo I asked him to send me a couple of years ago. “You don’t owe me anything else.” I was paying him, of course, but during one session, he was nice to me in a way that was so unsettling, I started sizing up the shape of his shoulders, finding desire for the width of his arms. I was getting ready, I realized, to put out in return for kindness.

I wondered, when I noticed Sky’s shape at my house, if I was doing the same thing. But I also deconstruct and reconstruct relationships, along with everything else, all the time, so I wondered as well if it might be nice to add platonic petting or smooching to our types of interaction.

He’d called me Sweetie. Then he called me Baby. He put his hand on my back once and consistently paid close attention to me, and I have so little experience with being appreciated without being obligated.

“I can’t always tell if I want to touch people because I have to or because I want to,” I told him when I asked if we were flirting. I’m getting better at it. And some touch, you just don’t know how you feel about until you feel it. In May, at Beltane, I declined sex with a (trans) person who asked, but I was open to lying shirtless on top of them. When we then kissed, I felt immediately that it wasn’t a form of contact I wanted.

I had strongly suspected that would be the case.

Even though I thought we wouldn’t spark, I was interested in putting my lips on Sky before he paid the tow truck, which he’d called and arranged himself—the type of caretaking role I’m used to occupying. While we were waiting for it to arrive, the passenger-side wheel of my home hanging delicately off the side of a collapsed embankment, I knelt on the ground and counted our blessings out loud, our health and our miraculous trans bodies and our integrity. In his house, waiting still, I offered a hug and we stood, holding each other and breathing deeply, coming together in the crisis rather than sniping, or distancing, or coming apart.

EARLIER THIS YEAR, I went to a trans support group. I’ve been to lots in a crowded city in California, but this one was at a smaller-town Washington venue that had a parking lot being used exclusively for the meetup. Pulling up to it on my bike, I surveyed all the cars, and felt something like: Awwwww.

They have cars.

They being trans folk. Like I don’t know trans people who have cars. Which I definitely do.

We deserve nice things. We deserve regular things. We deserve to not feel like we have to have nice or regular things to be valid and acceptable human beings. I deserve to not have to convince myself, every time I buy a nice thing, that I deserve it, and to not feel like nice things are impossible for me, whether I’m kissing anybody or not. I deserve to not burst into tears in Sky’s driveway because he’s the only trans person I know who possesses a house and extra money for an emergency while living a single gay life.

He didn’t want to kiss, because we don’t have that chemistry. I wanted to try anyway. I wanted to fill a space that’s left by having left everyone else in my life to whom I said no, but who insisted anyway. To whom I tried to be close, but couldn’t be without giving something up. Friends. Exes, some of whom started as friends.

My father.

Last night, I couldn’t sleep. I saw an image of blood gushing out of a hole in my heart every time I closed my eyes. A younger part of me—along with an older part of me, whom I don’t see or sense often but whom I know is a tremendous resource—kept trying to close the wound, covering it with paper, pushing the edges of my ruptured skin back over top. They gave me love to seal it with. That’s what it needs to hold, and that needs to come from me.

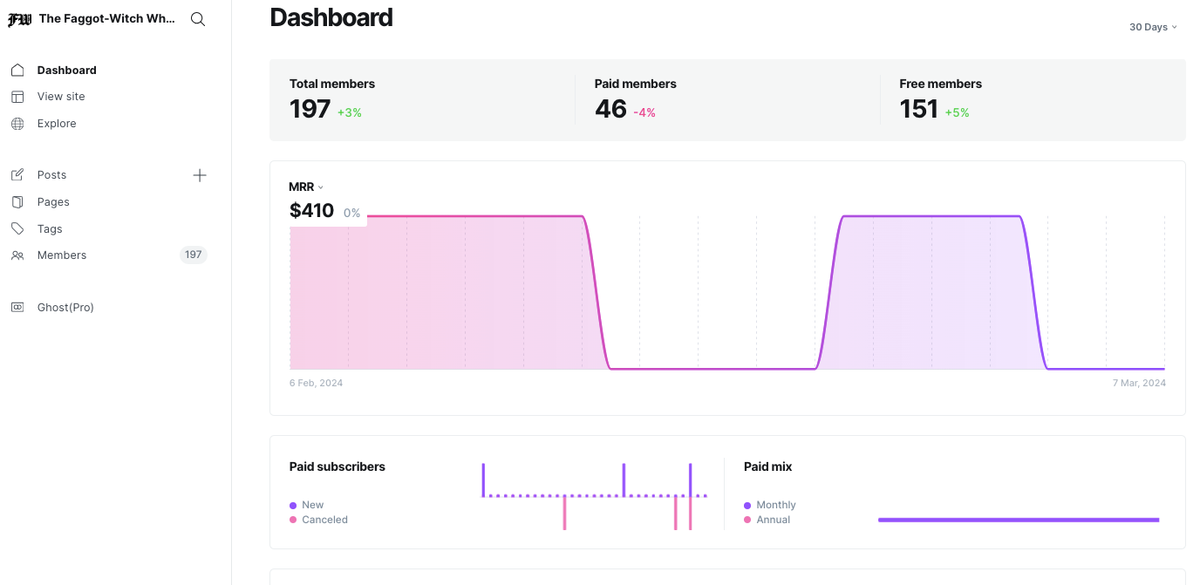

Member discussion