A Refutation of Dave Chappelle’s Transphobia

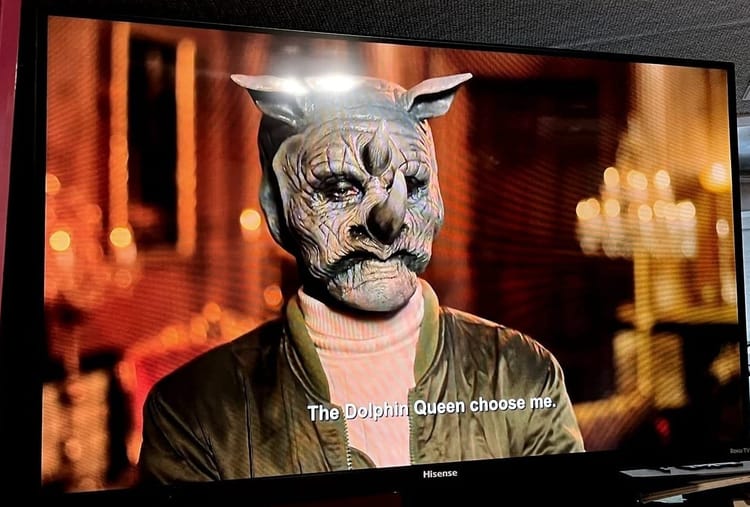

Two nights ago, I made the mistake of turning on “The Dreamer,” the most recent standup special from Dave Chappelle. I hadn’t watched it previously because his specials are virulently, volubly transphobic, but I naively thought that this one’s 2024 Emmy nomination for “Outstanding Variety Special” might mean it was less so. Instead, it was breathtakingly so, from the opening bit to 12 minutes in, when I had to turn it off. Even after saying, following his first massively depersonalizing joke, that he wasn’t going to “punch down” at trans people much, he was still at it. And the crowd was still going wild. Feeling stomach-sick and renewably daunted about how much hate I live among, I opened my computer and finished this piece I’ve been working on for two years.

Love and trans magic 🖤 G.

THE FIRST TIME I saw an endangered owl, I was with an ex-boyfriend. We were walking on a trail in a not-at-all-remote wood in San Francisco’s North Bay, chatting nonchalantly, until his eyes suddenly went wide along with his mouth. His arm went out to stop me. He pointed.

The owl sat on a low branch, right out in the open. It was tall, approaching two feet, and calling casually if insistently to its mate. It seemed unbothered, both in the calling and by us, staring back from 15 feet away. My ex and I whispered to each other, mostly Oh my god. The owl blinked, very, very slowly.

The next time I saw an endangered owl was the next time I was walking through the same forest with the same boyfriend, months later. It was in a different tree, and this time I was the one who spotted it, and this time, there were two of them. They sat, wing-to-wing, on a high branch, unmoving except to look at us. We stood on the dirt path, gaping at them.

There are two thousand pairs of those owls left in this world. We’d happened onto one of them.

I went to that same trail a hundred times by myself. I never saw any owls, not on my own.

On my deck at the apartment I lived in then, there were flower boxes, one of which was full of California poppies. Their iconic orange blooms mature inside of a slick green sheath, which slides slowly off the compressed petals in one intact, horn-shaped piece, dropping an empty husk off the top to release the sunshine burst beneath. I only know that because one day while that same ex—who is also trans—and I were sitting close, talking and cuddling on a piece of patio furniture, I noticed one of the sheaths starting to shift upward, revealing a hint of orange at the base.

I called my ex’s attention to it, and we watched, awed, as it slipped up, and up, and then entirely away, a brand new blossom unfurled.

When two or more trans are gathered—isn’t that what Jesus said? I think it’s what he meant. God is in their midst. God is their midst. A couple of years ago, I went to a park with a trans friend who took his dogs to that park regularly. But never, until we sat down together on a bench that day, was he boldly approached by an entire pack of otters.

They edged closer and closer to us, the two of us incredulous, the group of them so cute and eventually so close that we actually got a little scared of them.

“This happens,” I told him, convinced by then—“this” being miracles—“when there’s more than one trans person in a place.”

“YOU FEEL MORE like breathing than breathing does,” I told another ex-boyfriend, West, last fall, gasping with awe. I can’t remember which night of our kissing it was, but his exhale into my mouth was like extra oxygen. Like the ionized air around a waterfall, all refresh and soothe. Buoying. Filling.

The next week, we walked to a maple tree and spread a blanket beneath it, taking off one item of clothing at a time until we sat naked and close, facing opposite directions. The outsides of our right hips pressed together.

Spent maple leaves rained down around us, though there was no breeze.

I HAD A sense when I embarked on this RV-buying journey that I was reclaiming my right and ability to just move around Earth, which had felt stripped from me when I started transitioning.

When, suddenly, people had started talking to me like I couldn’t.

Like the nurse in Oakland who had burst into breathless tears at my mere arrival to a doctor’s appointment, then refused to do my intake, saying, “I don’t know how to talk to people like you.”

I’d had the vague idea that I would drive, would need to drive, this RV to every corner of this country just to prove to myself that I could. Whatever it took to remind myself that I belonged, in even the least trans places I could find.

I’d already done this. I’d done it in Hungary, one of the most trans-antagonistic places in Europe. I’d done it in a BMW dealership. Even inside the bubble of the Bay Area, where I lived when I bought Bessie, I didn’t have to go far to be the only trans person in a place—I’d been that almost every time I so much as went to the grocery store. I was it again when I started showing up at RV parks.

Strangers there were not just fine with my presence; at one, they kept giving me presents.

Welcome, welcome, we’re so glad you’re here, they seemed to want to tell me.

But it wasn’t cis people, really, with whom I’d long most longed to belong.

I could feel the stars move as we brought our bodies together in sex, a swooning shift in the sky when his tongue touched someplace tender; we felt fountains of pure adoration, swelling and pouring into him from inside me, when mine did.

“YOU TWO ARE beautiful,” said a cis woman unknown to me a couple of weeks ago. She’d come up behind me, her hands suddenly on my torso, in a waterfront bar on a sunlit Liberty Bay. I was sitting at a pub table with a date—a first date—and whether she was clocking either of us as trans or just seeing that we were gays or both, I can’t say. She repeated that she just wanted us to know how beautiful we were, while the other lady and some men in her party stood by, smiling but uncomfortable.

Later, I was texting with this date, and then my trans doctor texted me about some logistic thing, and suddenly there I was: texting two trans people at the same time.

What a dream.

I have googled, in moments where I’m desperate to watch TV without being dehumanized or erased, “tv shows about a trans person doing anything.” I have written my own headlines about a trans person doing something. I have been, and remain, desperate for trans immersion. Those text conversations weren’t remotely the first time I’ve been talking, in text or in real life, to two other trans friends at once, but every time, it’s like air that reminds me I’ve been suffocating.

“I DON’T WANT to hear that love isn’t enough,” my second husband sobbed angrily seven years ago, shortly after I got down on one knee in front of him and proposed divorce. He’d already said a calm, resigned yes, sitting there on the couch, but as we continued to talk about it and the grief set in, so did his defenses.

He was pissed. We loved each other. We were in love. That should have been enough for forever.

But it wasn’t. It isn’t.

“We need to go back to being friends,” I told West, the day after we were naked under the maple. We had been uplifting each other for a couple of magical romantic weeks, inspiring each other to eat well, to rest, to receive.

But in the long run, we were collectively too under-resourced to become boyfriends, I told him.

“You’re hard to keep up with,” he’d told me once. Over many years, I had turned myself into an emotional-processing machine, and where West avoided feelings, I dove in to investigate mine as hard as I ever had any story; it’s a practice, and it takes practice—tons of it. West’s and my combined stresses of homelessness and poverty; of wild suicidal ideation and intersecting marginalizations; of vast histories of violence overwhelmed us each on our own. Together, they would compound and require even more work. More work than we could do.

“You would know,” my friend Ryan said. It’s a dubious distinction, being an expert in relationship doom. But there are limitations to what two people can handle. Even two trans people.

Especially, in this anti-trans world, two trans people.

Cheers, queers.

Donations to this site support my life and gender expression, including manicures that have the added benefit of scandalizing men in public restrooms. 🤍

TIp 💅“You learned your lessons the very hard way,” my second husband said when we had lunch together the day after I told West we needed to not date. He—my second ex-husband—wasn’t mad anymore. But West was, now. Despite what I knew, despite the boundary I’d set, my desire to stay close to him warranted whatever overstepping it required.

It was ultimately me who asked him to be boyfriends. Then it was me who assured him when we encountered friction, and when we ended up in a fight about once a week, that we were navigating it well: with talking and listening, without yelling or insults, with genuine efforts to stay open. “We are doing so good,” I was the first to say. I repeated it many times after that.

“We are doing so good,” despite our traumas, the almost inconceivable odds against us. Considering all that—frankly, compared to a lot of people without all that—“We are doing so good.”

But when he was upset, he kept saying: We weren’t. Maybe my bar was too low. Hard as I tried, with all my energies and experience and skills, draining and losing myself in the process, he started singing a refrain similar to other boyfriends and husbands I’d picked in a lifetime of my saying to myself—of the whole world saying to me: You need to be different.

IN JUNE, I went to a small-town Pride near where I live. I ran into three different trans people I knew, literally almost colliding with one of them. But each time, I didn’t recognize them at first.

All I saw was shimmer. It’s the kind I’ve seen before in trans faces, but this time, each time, it was so bright that I couldn’t even see my own friends. I don’t know if they were shining particularly bright that day, or if I was more sensitive to it, or both, but when I looked at them, I saw just a familiar sparkle. Just magic.

All I saw was god.

Before West and I broke up, we were in the squish one day when I lay back with a lungful of indica and found myself suddenly, surprisingly tripping. I saw that, a long, long time ago, the two of us had created the universe. It explained why sometimes I could feel the stars move as we brought our bodies together in sex, a swooning shift in the sky when his tongue touched someplace tender; we felt fountains of pure adoration, swelling and pouring into him from inside me, when mine did.

But we were trying to keep it together on a planet where we’d both survived more crimes than anyone could count, with a fraction of what we’d needed.

And, still. Together, we had more good days than we’d been having apart.

In my indica trip, I could see that as far back as creation, there was something broken in our union. We didn’t mend it together, not then, and we didn’t mend it now. Maybe we were meant to mend it separately; maybe we were meant to mend only ourselves. But how we were together, however it may have been not great for either of us, was already better than anything I’d imagined for myself.

My date from a few weeks ago, he was kind, in a way that is so unfamiliar and unsettling to me, I had to schedule emergency therapy about it. Talking and thinking about him, I found myself having a hard time recalling his face. I remembered steady, attentive eyes. Teeth flashed in an unguarded burst of joy. I could feel him more than I could see him—the salve of home in the most ancient sense. Of familiarity, of divinity. My future is unfathomable, but I gain increasing trust in how unfathomably better it might be. Because god is change.

And change, that’s trans.

Member discussion