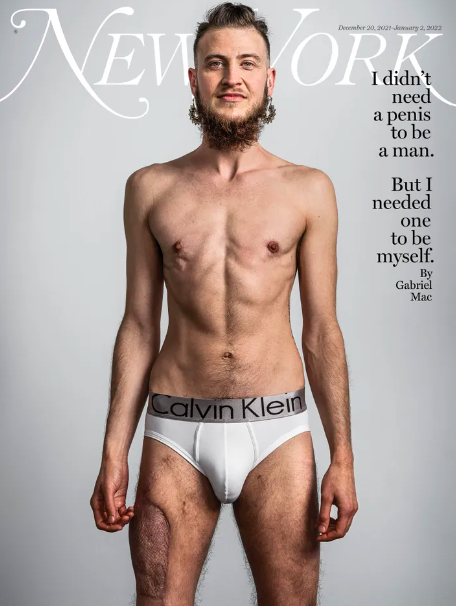

My Penis, Myself

The following is a free reprint of the cover story that originally appeared in New York Magazine.

ON THE DAY I heard that my penis would be huge, I sobbed.

In the car outside the doctor’s office afterward, I bent my torso in half and bawled, my face against the dashboard, my boyfriend petting my back to console me but confused. Isn’t it good news that they can do it?—like: At all? And obviously, yes. It was. Growing up without one, I’d thought or maybe convinced myself that mine would grow in later—to the extent that when I see a woman in tight pants, I still often instinctively think, Where is her penis?—but my period at 12 aptly, agonizingly bled to death that increasingly implausible dream of reconciling with life, with God, that he wouldn’t make me like this and leave me like this forever. So the news, 28 years later, that the agony was going to be over—abundantly over—was a bit much to take in.

I fixated instead on the information that a pert little average-flaccid package was not an option for me. (If I even wanted that.) (And did I?) When I’d asked the surgeon how big my impending penis was going to be, he could only guess, pointing to the reusable water bottle in my hand, a metal cylinder nine inches in circumference: “Smaller than that.”

I was so different from everybody else already.

I was already always so different.

Phalloplasty in general, it was clear, was hard for people to accept. “Well, I will love you no matter what, sweetie,” a cis female best friend of mine said when I told her I was transitioning, years before—“as long as you don’t get a dick.” One flatly demanded, “Don’t get a dick.” It was, another transmasculine person I used to know said, disgusting, insane to want and to have a surgeon make a sensate phallus out of your arm or leg or somewhere and Frankenstitch it to your body, to go so far out of your way to opt in to a tool, perhaps the tool, of so much suffering. Most transmasculine people didn’t get one. The seminal print transmasc magazine was named after not getting one: Original Plumbing. I saw transmasculine support groups shut down and go silent more than once when someone brought up the procedure, and later, when I was that someone, I was twice invited to leave “with other people who might want to talk about that.” Whatever magical spectrum of unicorn gender expression was otherwise being embraced, it ended firmly before needing a socially, culturally, politically, historically, personally, emotionally, medically complicated dick.

But I did. And I couldn’t outrun it any longer. Literally: The day I gave in and admitted that for me it was penis or death came after a last-ditch bout of denial in which I drove 1,400 miles in three days only to have to acknowledge, devastated, at my destination that I couldn’t avoid it anymore.

So there I was then, finally, showing up to online specialized transmasculine support groups for people seeking or recovering from phallo, between hours spent hustling to call (six) surgeons’ offices about consults and my PCP’s office (19 times) for referrals and my insurance company (17 times—that I wrote down, anyway) for the necessary authorizations. And here they were, these trans and nonbinary people of many races and locations, coming together to try to hold one another’s questions and fears about which donor site on their body to use, and how the site had (or hadn’t) recovered, and how much sensation they had (“My whole dick feels like a giant clit!” one elated guy described his rare, very best-case outcome once to widened eyes all around), and what size testicle implants they got if they got testicles (which are optional) at all, and which surgeon they went to and when could you go back to work and who in the world took care of you, and did anybody else have this or that or a whole series of fistulas or strictures around their new urethral hookup that rerouted their pee and is also optional, and did anyone else just leave their urethra where it is? Once, a pre-op 52-year-old Black man who was struggling with money and his disability and insurance asked if having a penis was really going to make a difference, relieve any of this pain he was barely surviving, and I watched as the post-op group members calmly assured him that, yes, it would. If he could just hang on, hang on, hang in there.

“It gave me a little more hope,” he told me later, “to keep going.”

“I would rather have died on the table than not had the surgery,” one Korean American guy with great sweaters responded (and, like everybody here, gave me permission to repeat), to a chorus of nodding Zoom heads.

It has happened at least once that someone did die. I was fully ready to, by which I mean I’d just spent nearly the last of my savings, which I’d burned navigating the emotional-mental-social-medical-legal-extreme-marginalization mindfuck shitshow of transitioning, on a burial plot just in case. One of the nodding heads in the group belonged to a nonbinary white person who was still horizontal in recovery from having had, a week prior, the worst happen, which was that after their procedure, in which all the fat and skin had been stripped from their left forearm from wrist to nearly elbow, along with major nerves, an artery, and veins, and then shaped into a tube and connected, in careful layers, to skin and blood vessels and nerves in their pelvis, their new penis had failed.

It died. On them.

But here they were, already getting ready for their surgeons to harvest a whole other part of their body within the month with zero hesitation. Because those three days they’d had their penis, they said, before being rushed into an eight-hour surgery that couldn’t save it—the feeling of it, even just for one moment, even still bloody and painful and packed with stitches: worth it. And I understood that immediately when, after a yearlong surgery waiting list and a deep quarantine and an anguished prerequisite COVID test I would either pass or lose my date over, I woke up last December in a hospital bed and before even glancing toward my lap, the room spinning from anesthesia and my lungs partially collapsed from four and a half hours on surgical ventilation and hundreds—plural—of stitches and a 40-square-inch hole in my thigh where I’d been skinned down to the muscle, I could suddenly feel, in a way I could never have fathomed, that this was what being alive was.

THERE'S A SCENE in Disney’s original Dumbo when the child elephant’s mom cradles him in her trunk and sings to him, exuding love. Quietly, but wholly. As a kid feeling utterly unheld by this world, I hated it.

As a grown man in a hospital bed, chest loosely draped with a gown in a low-lit December room, I looked down in the direction of a penis I’d assumed would be covered in bandages—but then there it just was. Laid out at an angle toward my left thigh, propped on a green cloth. And I, awed and heartful and weeping, sang that song to it.

Ba-by mine, la na na naaaaaaaaa.

I don’t know the words.

Baaaa-byyyy mine, na na na naaaaaaaa.

La, laaaaaa, la—na na na naaa,

La na na naa, baby of miiine.

While I’d been sleeping, two microsurgeons, a reconstructive urologist, a surgical fellow, and a surgical resident had, among other things, cut a seven-by-six-inch rectangle out of my right anterior lateral thigh. They’d taken all the skin and fat, plus one big nerve and some veins attached to the muscle, and connected the skin to itself in the shape of a phallus. Then they slipped the whole thing under two of my thigh muscles, pulled up out of the way with a steel retractor, dragged the phallus across my groin under the skin, and pulled it back out into the world through a hole cut in the skin over my pubic bone. They connected the new penis’s nerve to one of the nerve bundles in my native penis, which some people call a clitoris (embryologically, the cells are the same), which they’d cut free of its ligaments, then skinned, then tunneled up under the skin and out to the landing site of the new penis, the base of which they joined to the base of my pelvis, putting me all together with sutures, some finer than a human hair.

“That penis,” Dr. Bauback Safa, one of the microsurgeons, said when he came by after to see me—to see us—“looks perfect.”

He was talking mostly about blood flow. He did not mean that, with its fresh stitches and a round, bloody hole at the top where the skin would eventually close together, it would look like any other penis at the spa. But also, it was a lovely shape. Dr. Safa had correctly estimated that the width—which can be debulked with further surgery but is initially determined by skin and fat thickness—would land on the very but not spectacularly girth-y side. The length I had been able to pick. Each surgeon I’d consulted with had asked what I wanted, then nodded mildly and written it down, breezy as a waiter. My instinctive answer was long, even though I knew it would be that long all the time: While neophalluses can be implanted with erectile devices that change their stiffness, they do not change their size.

“That’s a lot of all-day D,” I’d said to the reconstructive urologist, Dr. Mang Chen, during our pre-op visit the week before. (He gave sort of a friendly, unfazed shrug.) I’d been saying it to myself, too, for months as I waited for my surgery date, wondering why I wanted so much, questioning if I should have less by some, by half, indeed like your average, unremarkable soft penis at the spa (listen: I’m Hungarian; I’m essentially made of hot springs). While the more common option of using flesh from forearms, which are generally slimmer, was barely viable in the case of my apparently bizarrely fatless ones, it was technically still possible, and though that site hadn’t felt right to me even before I was told it would make an appendage without any substance, I considered it anyway.

I second-guessed myself constantly. I’m asexual (yes, you can be asexual and have a boyfriend), and what that means for me is my penis was just for me. So what was even the point of having a lot of it? Was I greedy? Crazy? Weeks before my procedure, I got a block of clay and sat meditating and molding by feel, letting my body answer. The resulting phallus was the exact size I’d been requesting. For days, I lay on the floor on and off in the sunlight coming into my living room, asking my ancestors and transcestors for guidance. Some people might kill for this kind of access and choice. Certainly many, many, many, many people have died in the fight for it. One night, I woke up from a dead sleep, and all I heard was: Take the big dick.

So I did.

And it was perfect. Not in the way I’d been trying to be perfect most of my life—catalogue-ready, ideal to everyone else. It may not have looked perfect by the assessment of every San Franciscan in the gray-white city outside my hospital window, and it was clear to me that it was—that I was—distasteful to some of the hospital staff, even though, with the preponderance of phallo surgeons in the Bay Area, they see multiple new penises every single week. One of my surgeons asked me at some point if I’d want to follow up later with surgical girth reduction in case this here wondrous member we had conjured from fucking nothing into warm, space-displacing reality wasn’t yet the fit that would stop the deafening five-alarm bereavement scream that had ricocheted around my insides incessantly since birth.

But the screaming had stopped. In its absence, I couldn’t read or watch TV, which felt overstimulating and loud. I listened, still, to the quiet. Breathing.

For five days, I lay in a hospital bed without moving. No visitors: COVID. Every day, twice a day, someone came and injected anti-coagulating pig-intestine derivatives into my abdomen so I wouldn’t die from a blood clot, my belly becoming a graveyard of needle-punched bruises. Three times a day, I ate, increasingly impressed and concerned that none of it was exiting my colon. People intermittently emptied my giant catheter bag. Occasionally, a team came and jostled me onto my side for a bit to prevent bedsores, each time the pain like being stabbed everywhere at once despite the on-demand Dilaudid and consistent Oxy. And once an hour, to ensure the vessels were thriving, a nurse came and put a pencil-size Doppler rod to my penis to check its pulse, and we listened together to my blood coursing through it, an ultrasound-heartbeat swoosh.

It was alive.

Some people want it all

But I don’t! Want nothing at allll

I do know the words to this song.

If it ain’t you, ba-by

If I ain’t got you, ba-by

After my discharge, which included a grueling car ride wearing mesh hospital underwear packed full of gauze to keep my penis propped as close to perpendicular to my body as possible, I spent the first hour in bed singing top-volume falsetto Alicia Keys to my penis.

So you can imagine my heart-stopping horror when I woke up that very first night to find that my penis—propped and carefully angled so as not to kink or damage the blood vessels that had been relocated through my leg and groin to sustain it—was cold.

I pressed a finger to the skin and let go, watching the color return. It’s supposed to happen quickly—but, a brief document from the urologist’s office said, not too quickly. What was the right speed? I texted the microsurgeons’ director of transgender services, a nurse named Logan Berrian, but it was 1 a.m. I Googled frantically, though I was already well aware of the dearth of available useful information about phalloplasty. Was the room just cold? How cold was too cold for my penis at this stage in its life? Did I need to go to the emergency room back over the Bay Bridge in San Francisco? Have a surgeon awakened and brought in? My right leg was in a full brace from hip to shin because my blood vessels, unlike most people’s, had turned out to require deep dissection of my rectus femoris muscle to excavate, and moving around was slow, difficult, also scary, often bleeding-causing agony. I pressed a finger to the skin again. And again, watching. Blood was returning. Blood was flowing. I spent the next seven hours watching over it, as if it were a troubled newborn, making sure.

“It’s okay!” Berrian texted me back at 8 a.m. It’s only an emergency if it’s cold and the “color is changing to a white/blue/gray/purple.”

On discharge day five, I woke up with a six-square-inch pool of blood seeping through three layers of bandages from the donor site (“Fine, nothing unusual,” came the text back), which during surgery had been covered with thin skin shaved from my other thigh with an instrument like a motorized cheese slicer, then laid over and stitched into the edges around the exposed muscle of the donor hole. On day seven, blood soaked through two additional layers of bandages and another of gauze. (“Looks good,” the doctor said when I had my friend emergency-drive me back to the city.) Every morning, I got up, after trying to sleep perfectly still on my back with my penis propped and my hips and my legs aching fire, and hobbled with the help of a cane to the toilet, where I used one hand to keep my penis level and the other to reach over to the sink and fill a bowl with warm water, then slowly, gently wash my genitals. Still, my whole lap smelled unrecognizable, not-human seeming, like a cross between hospital air and a livestock barn. (“Everyone freaks out about that,” a different nurse said over the phone, laughing a little, when I asked if I was okay.) For more than 30 days, my donor thigh oozed fibrinous fluid from wet holes, which became big, open red gashes where the skin graft hadn’t taken. (“It’ll close. It’s just like any other wound,” said Dr. Andrew Watt, the other microsurgeon, at my fourth weekly post-op appointment—to which I’d responded, “Is it?”) My other leg, the one the graft had been taken from, had dried blood always flaking from the sometimes burning, four-by-seven-inch skinned site trying to regrow itself, and at some point my penis started to separate a bit from my body.

It was a tiny gap, the littlest hole, between the base and my pelvis at the underside where the stitches hadn’t closed, small compared with many people’s wound separation, as it’s called, which happens “90 percent of the time” and is self-resolving. But it was so distressing that I mostly just refused to look at or touch it for two weeks, the panic spreading harsh electricity through my whole torso, even worse and for much longer than the time I stood alone in my kitchen, hyperventilating, holding my penis level in one hand and my phone in the other as I Googled, What does gangrene smell like?

“The whole process is constant body horror,” Berrian said at one point—after he’d told me that the penis-tip discoloration I was worried about might just be sloughing tissue that’s dying off, which is also fine. And this was a recovery with no complications that required surgery. The overall proportion of phalloplasties that need surgical revision, while lower for some surgeons (including mine), is about one in two. The highest number of corrective follow-up surgeries needed by anyone I know personally is 12.

This is what some people do for their penises. And though phalloplasties that survive a couple of weeks tend to survive, period, through all manner of regular penis life and then some, I was hysterical over the possibility that mine wouldn’t. If it died, I felt certain, I would die. I had pushed myself up against the absolute limits of enduring life without it, and I wouldn’t go back to before.

I couldn’t go back to before.

One day, in that first week out of the hospital, I stood with my leg in a brace and my weight on a cane, thudding the tip of it rhythmically into the floor while listening to upbeat Billie Eilish. It was the closest thing to dancing I could do, but I understood then, for the first time, that what dancing is about is that Our. Bodies. Are. Spec. Tacular.

Another day, I lay on a couch staring into a shaft of sunlight coming through a window, listening to “Can’t Find My Way Home” on repeat, tears quietly streaming. The sensation was foreign so a little bit scary, but I think the feeling I was feeling was what people mean when they say calm.

At other moments, I was so overwhelmed by floods of repressed rage and grief that all I could do was open my mouth and start screaming.

When you release an animal you’ve been keeping too long in a cage, a therapist of mine used to say, it tends to emerge snarling. “It all comes swirling out after surgery,” oliver flowers, a caregiver with T4T Caregiving, an all-trans caregiving service, texted after I reached out one night in despair. Barely able to move, I tried breathwork and meditation and a soothing bedtime-story app before, out of desperation, I started making up lyrics to “The Sound of Silence” (Hello, penis, my new frieeennd), cry-singing out my struggle through an epic that ended up probably 17 verses long. “So many of us have had to put up walls of protection to get us to this point, then the intensity of the experience breaks it all down,” flowers said. I don’t use the words trauma or torture flippantly; I know from both. And you don’t escape four decades in a body that feels simultaneously dead and like an eternal wellspring of agony without either. “It’s just that we’ve had to hold in so much for so long — and this process frees us from that … but not before feeling it all.”

Around day 50, I realized I couldn’t remember the last time I’d thought about killing myself. The first story I ever wrote—in my head, building chains of memorized sentences, same as I compose to this day—was about committing suicide by walking into the Atlantic Ocean. I hadn’t yet started kindergarten.

Able to move around a little better, I washed my bathroom sink. Not the whole bathroom—just the sink. And though I have always run a tight bathroom, I stood back and beamed at it, at myself, as though I’d just discovered penicillin. Almost every time I made myself a plate of food, though I’d been feeding myself (and sometimes additional adults/husbands) for decades, I said, often out loud, “I did that!” Everything was a miracle. Everything was different now that I lived this existence I’d been violently and thoroughly socialized to believe was an impossibility. At day 60, my open wounds finally, unimaginably, closed.

In the beginning, the nerve connection growing in slowly, I could feel my penis in my hand, as I incessantly had to hold it while limping around my apartment, or against my wrist as I hunched over to rest it there like some kind of penis sommelier, freeing my fingers. But it couldn’t feel me.

“I’m always bashing it into things,” I told someone early on. After it was healed enough that I could finally stop propping or holding it, I’d walk up to the kitchen sink to do dishes and bash my penis into the cupboard knob. Raising my hands to gesture while I talked, I’d drop them back into my lap and punch myself in the dick—which, before long, I definitely felt. For a while, I was most comfortable relatively nonconstricted (I see you, Jon Hamm), and I sent a barrage of texts to a guy I knew with similar endowments asking where he put his, spiraling about how I was never going to fit into any pants or underpants or, ultimately, society. One day, I rounded a tight corner into the tea aisle at the grocery store and, misjudging my proximity to a display table, knocked a wine bottle over with my dick, feeling a hot flush of embarrassment that I didn’t know the dimensions of my own body.

One night in the shower, though, my right thigh, finally in one piece but still unfamiliar, caught my attention. I had a (trans) friend who said once that his reaction to seeing thigh phalloplasty scars was “That’s a nice penis. But look at your leg.” I looked down at it: a raw, raging pink rectangle, scaly from the hole-punching machine they’d fed the skin graft through, flesh made mesh to cover the exposed muscle, and another long line of scar like railroad track angling toward my groin. And it struck me, immediately and only, as another incredibly specific thing I got to love about myself, and I collapsed into the wall, sobbing.

"IT'S INTERESTING TO see how you’re different,” a friend of mine said ten months after the surgery, when I went to visit him.

It was possible, of course, that I was going to wake up different—in a bad way. Some of the best men I know don’t have penises, and plenty who do are hardly role models. I’ve been on the abuse/harassment/condescension/denigration/objectification/crimes end of enough penis-havers to have worried about it, however far back in my consciousness. I had a partner once who terrorized me about his sexual “needs,” and some time before starting to transition, I spent an afternoon on mushrooms crying against his dick, silently telling it I knew it wasn’t its fault. It was probable I was going to wake up more me. And I feared, from my most scared place, that would mean more harmful.

“There’s a gentleness,” my friend said about me now. “It was always there,” he added, having known me for many years. “It just wasn’t…first.”

No. It wasn’t. But when penis is self, as penis is a gift to self, it’s a gift, too, to others.

A few months prior, I’d sat on the couch with my boyfriend having a contentious and difficult conversation. At any other point in my adulthood, I would have shut down hard with defensiveness. That day, though, even still healing, wounded and broken and terrified that my leg would never really work again, I stayed soft and open and kind.

You, he said, eyes wide, are being so generous.

I was surprised too. As a child growing up in the Midwest in the 1980s, I never could have known, but somehow must have believed, that there was a way a man could, even frightened and unsure, stay grounded in love for himself. No matter how unexpected or unaccepted that self was.

A few years ago, a year after I started transitioning, I sat at a red light in my car, which I was getting ready to sell, and thought suddenly, What kind of a man doesn’t have a car? A belief I didn’t even know I’d absorbed from somewhere (an early episode of The Love Connection, I am almost positive) was floating around my consciousness, wreaking insufficiency. A year after that, I joined a gym, wondering if now that I was teeming with testosterone, I might enjoy gym workouts (answer: no. Every few minutes, the personal trainer I signed up with directed me to do an exercise, and every time, I thought, Why? Why would I do that?). One day, after my trainer had me pick up some dumbbells, I expressed doubts that I’d be able to press them. “You picked ’em up, you gotta put ’em up,” he said so automatically that I asked, “Is that what masculinity is?” (He laughed, surprised, before responding, “I guess so!”) Allegedly, masculinity isn’t the sound of my voice, because though its pitch (130 hertz, whatever that means) is “within the normal male range” (whatever that means), the overall effect, an actual medical doctor told me once, is female because I talk like such a girl.

It’s not a penis that makes someone a man, either. And a vagina does not make a woman. Most people who are having phalloplasty, though, do get their vaginas removed during the procedure. Broadly, I get it: I could not have gotten my boobs cut off fast enough, and I spent weeks before my 2019 hysterectomy up late in bed, hot and sleepless, fantasizing about the moment the medical-waste-disposal team at UC San Francisco would batch-incinerate my uterus, which swirled with dysphoria like nausea from the depths of my soul. But just as you might feel an automatic no if a doctor offered to cut one of your healthy arms off for you, when I thought about cauterizing, excising, and sewing closed my vagina, my whole body cringed: wrong.

“Do you have to get rid of your vagina?” I’d asked the first phalloplasty recipient I’d ever met when he came over to my house for macaroni and cheese one night before my first consult. He’d generously offered to share his surgery experience, and I’d maybe surprised myself by asking but definitely surprised myself with my response when he said no: I involuntarily fist-pumped.

Using plastic-surgery methods that were developed because so many people’s faces were blown off during the First World War, the first phalloplasty was performed in the 1930s. A couple of decades later, trans-surgery centers started opening at several American universities. But in the ’80s, most of the university surgery centers closed or went private, and by 2000, the going rate for a phalloplasty was $80,000, cash only. Those surgeons often held “a very rigid view of what our transition should be,” says trans elder, activist, and policy consultant Jamison Green; they aimed to make good, regular straights out of us, and it was known in the community that if you weren’t one, you’d better lie about it. They excluded people who had given birth because real men, Green says, “wouldn’t let themselves have kids.” One transmasculine pioneer, Lou Sullivan, wrote long letters to Stanford’s clinic for rejecting him because he was gay.

“I’ve been trying to just live without a penis for a very, very long time,” I wrote in a journal after my first consult in early 2020. “No one’s holding me back but me.” But that cliché isn’t true, is it? That’s a survival adaptation of the oppressed: to take on responsibility for their own suffering so they don’t give up against impossible odds or lash out in ways that further endanger them. The midwestern state I grew up in still explicitly excludes trans health care from state insurance coverage. This year, more than 100 bills in 35 states targeted trans people’s access to civil and medical rights. In 2020, to get phalloplasty covered in the great(est) state of California, which has legally mandated state trans health coverage since just 2013, in addition to the usual bullshit of spending a part-time job’s worth of hours and energy getting and then wrangling insurance and doctors’ offices and prerequisites, I needed letters from three separate medical professionals, not counting my three world-class surgeons, declaring that I wasn’t insane. Currently, there are only about a dozen phalloplasty teams in the whole country—mine started putting their world-class skills to phalloplasty use partly because they could get paid for it by insurance—and up until recently there was still at least one surgeon who wouldn’t allow patients to keep their vaginas, not because it was medically impossible but because he didn’t think it was right to have both.

“The pain is not just that I’ve been ignoring myself but that I still am,” my journal entry continues. But it isn’t true, either, that the attempt to erase my existence originated with me. One day, lying on my couch in quarantine before surgery, I watched a Ben Stiller/Eddie Murphy movie recommended by HBO Max—until the point when, apropos of absolutely nothing, a character makes a joke about a real-life trans guy who, in real life, was brutally raped and shot to death. Shortly after that, Hulu recommended a Keanu Reeves–Winona Ryder movie from 2018, in which Reeves’s character says trans people are deluded untouchables. While I was recovering, I watched a Jennifer Lopez rom-com from the same year, happily zoned out like a normal person until 29 minutes in, when she does a bit where she tells a guy someone is trans(masculine); the joke is that the guy used to have sex with that trans person, and now that he knows he fucked one, he is disgusted.

Months later, this latter scene popped into my head while I was making hummus and made me cry. I get messages like this in some form every day. In a break from working on this story, I turned on a hotel TV, and within minutes Chandler on Friends was saying he finds his transfeminine parent revolting. This is a recurring feature of this show, which I watched all through my teens. Seven months into recovery then, I felt, like all the other times, the knife of it through the center of my chest: You are not welcome here.

As I had with my penis length, I second-guessed my “unique surgical goals” (Okay but what if I did just let them sew up my vagina?) from the moment I knew they were possible, but the morning I walked into the hospital, I trusted my instincts. If there was anything I had learned in transitioning, it was that what was right for me was rarely what, according to my patriarchal, heterosexist, racist, capitalist acculturation, “made sense”—which, obviously, could only be to live as a sexually available cute-lady vessel capable of carrying white babies. It’s impossible to articulate and maybe even to know exactly why my vagina is integral to my power and my personhood. “I cannot wait to be more masculine so I can be more feminine,” I used to write in journals as I started transitioning and realized, though I didn’t quite understand why, that was what I needed.

An intuitive once told me that in a past life I was a priestess. Whatever it is that made me this, given, finally, the remarkable chance to embody it, which technically has been available since decades before I was born, I stopped withholding myself from myself, even if much of the world is aligned against who that is.

I’ve never seen or heard of a book or show character or even another person who is an asexual gay man with a penis and a vagina. But after I got out of the hospital, standing in the bathroom washing my hands, with most of my body, much less my genitalia, well outside the mirror’s frame, I looked up and suddenly, for the first time in my life, recognized my own face.

Not everyone does. Sometimes I get misgendered—sometimes even by people who are trying their best. Just last week, someone at the photo shoot for this article misgendered me repeatedly, not noticing at first, then, after I’d corrected him, cursing himself, apologizing sincerely. I took a moment outside, letting the loneliness sink in. Only days prior, I had been misgendered and responded, in a hard-dying habit, by blaming myself—if only my voice were deeper; if only I were less femme—instead of the systems that had worked to erase me and people like me for centuries.

This time, I refused to internalize it. There isn’t, I breathed deep, anything wrong with me. I got myself ready and walked on set and stood, nearly nude, compassionate and angry and proud. Whatever was happening around me, I was centered, in my body and in the shots I could see on the monitor, beautiful, accurate—perfect. Days before my penis’s first birthday, the warmth and weight of it lay against my vulva, each supporting the other, holding me.

Member discussion